Thinking Without Words

Photo by Terence Burke

Introduction

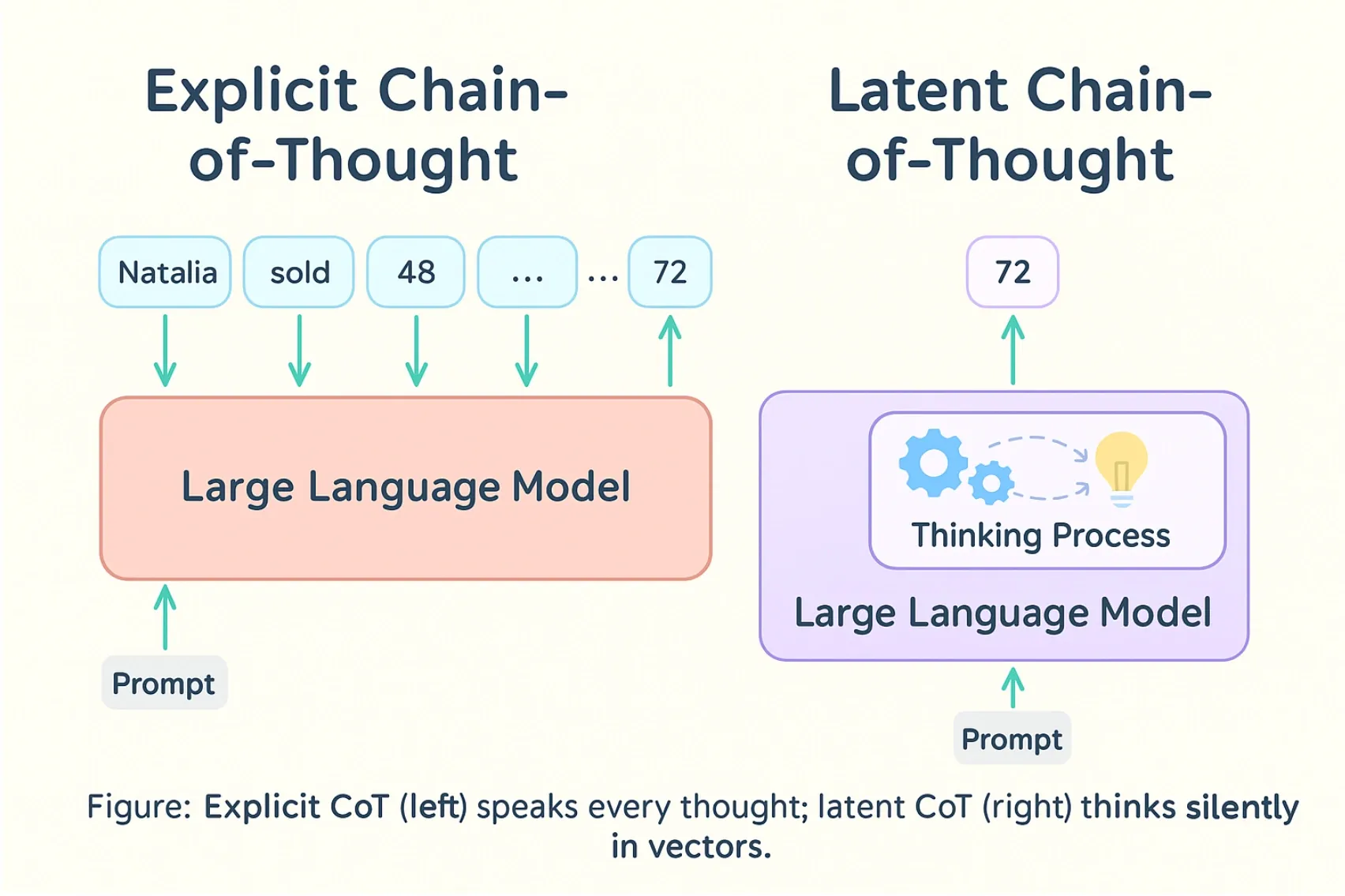

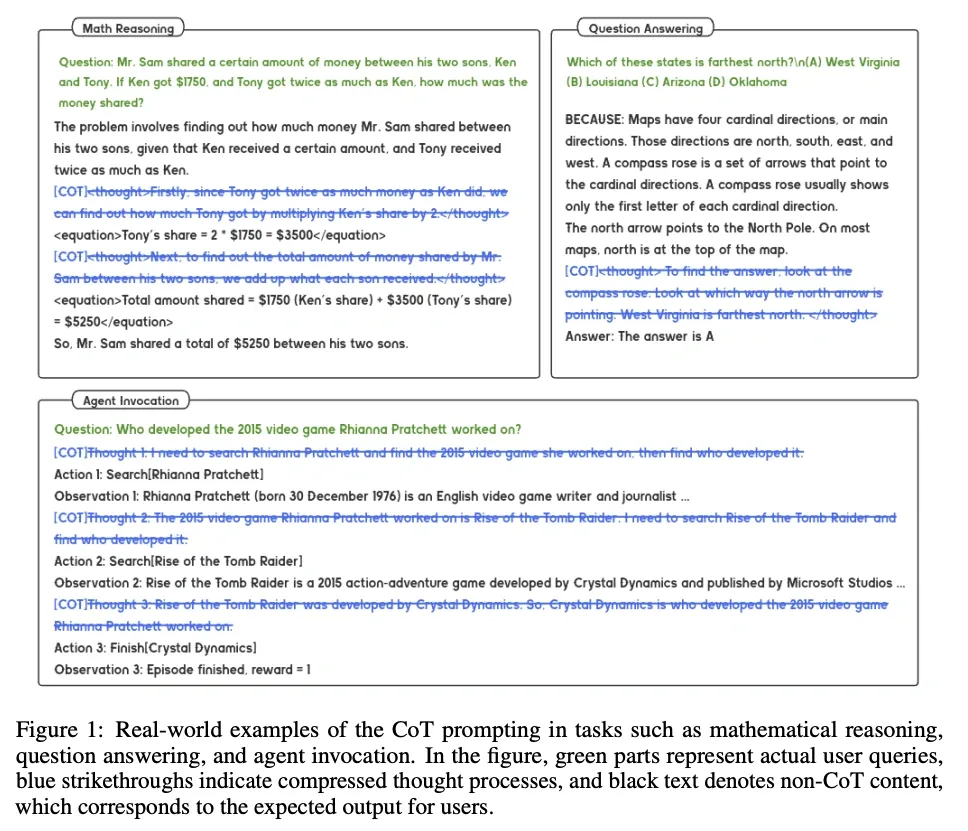

Recent “reasoning” models trained with reinforcement learning can get better results on tasks with verifiable answers (math, code, logic), often by generating long Chain-of-Thought (CoT) traces during inference. Those extra tokens help, but they also make reasoning expensive: the model has to express intermediate steps as text.

CoT is readable, but it’s also a bottleneck: every intermediate step is serialized into tokens. A line of work explores continuous latent reasoning, where intermediate reasoning happens in high-dimensional vectors (hidden states) instead of discrete language tokens.

This approach changes where “reasoning” happens (latent space instead of explicit tokens), but it also makes interpretability and evaluation harder because the intermediate steps are not directly readable.

Image inspired by the one from the paper Reasoning Beyond Language: A Comprehensive Survey on Latent Chain-of-Thought Reasoning.

Historical development: toward latent reasoning

Early foundations (2022-2023)

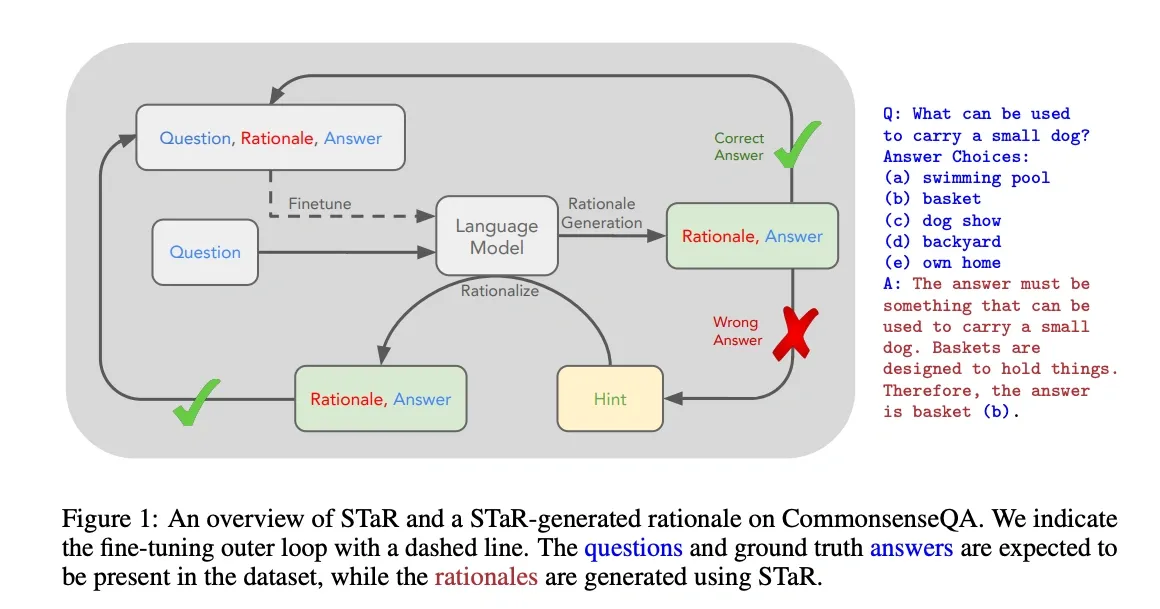

Zelikman et al. (2022) introduced the Self-Taught Reasoner (STaR), an iterative self-training loop: the model generates rationales, keeps the ones that lead to a correct answer, and fine-tunes on them. It’s still explicit, token-based chain-of-thought, but it shows how a model can bootstrap better reasoning from its own successful traces.

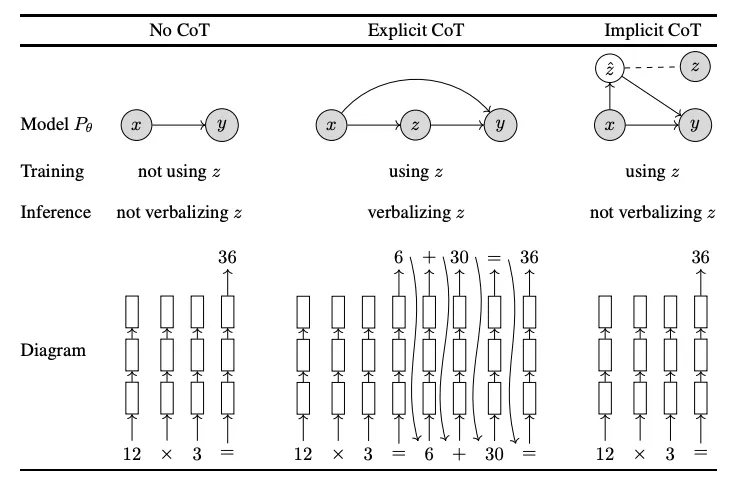

Deng et al. (2023) introduced Implicit Chain-of-Thought (ICoT), which uses distillation to train a student model to match the hidden-state trajectory of a larger teacher as the teacher generates an explicit chain of thought. The goal is to push the teacher’s step-by-step reasoning into the student’s layers. This can reduce inference time, but the paper reports a drop in accuracy versus explicit CoT, especially on harder tasks.

Interpretability work also asked whether models do multi-hop reasoning latently. Yang et al. (2024) found moderate evidence for latent hops, with higher rates for some task types. Their probes suggest intermediate structure can exist in hidden states even when the model answers directly.

The discrete token era (2024)

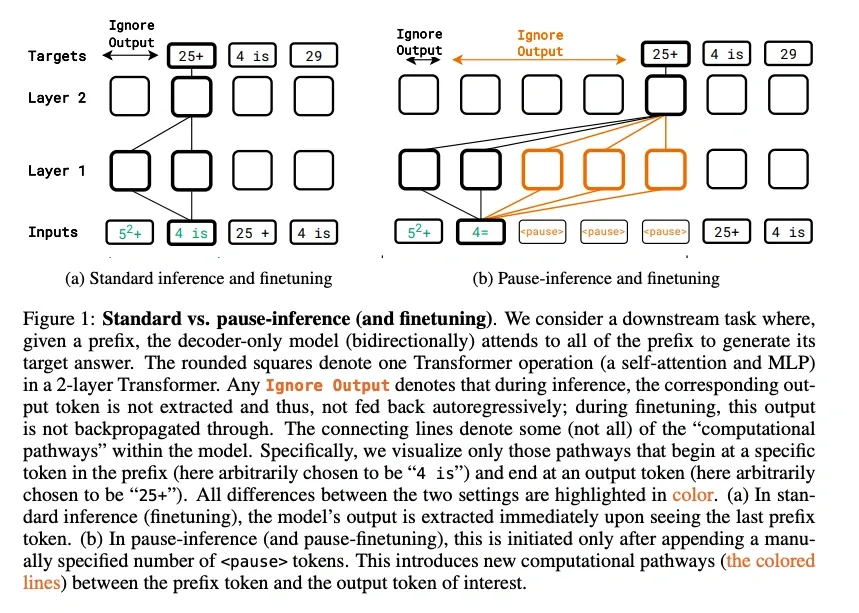

Another thread experimented with specialized discrete tokens to represent reasoning states. Goyal et al. (2023) introduced “pause tokens” that let models perform additional internal computation before generating outputs. These tokens are inserted in a fixed, non-adaptive sequence and act as computational placeholders: delay the next prediction, get extra compute, sometimes improve accuracy on logic-heavy tasks.

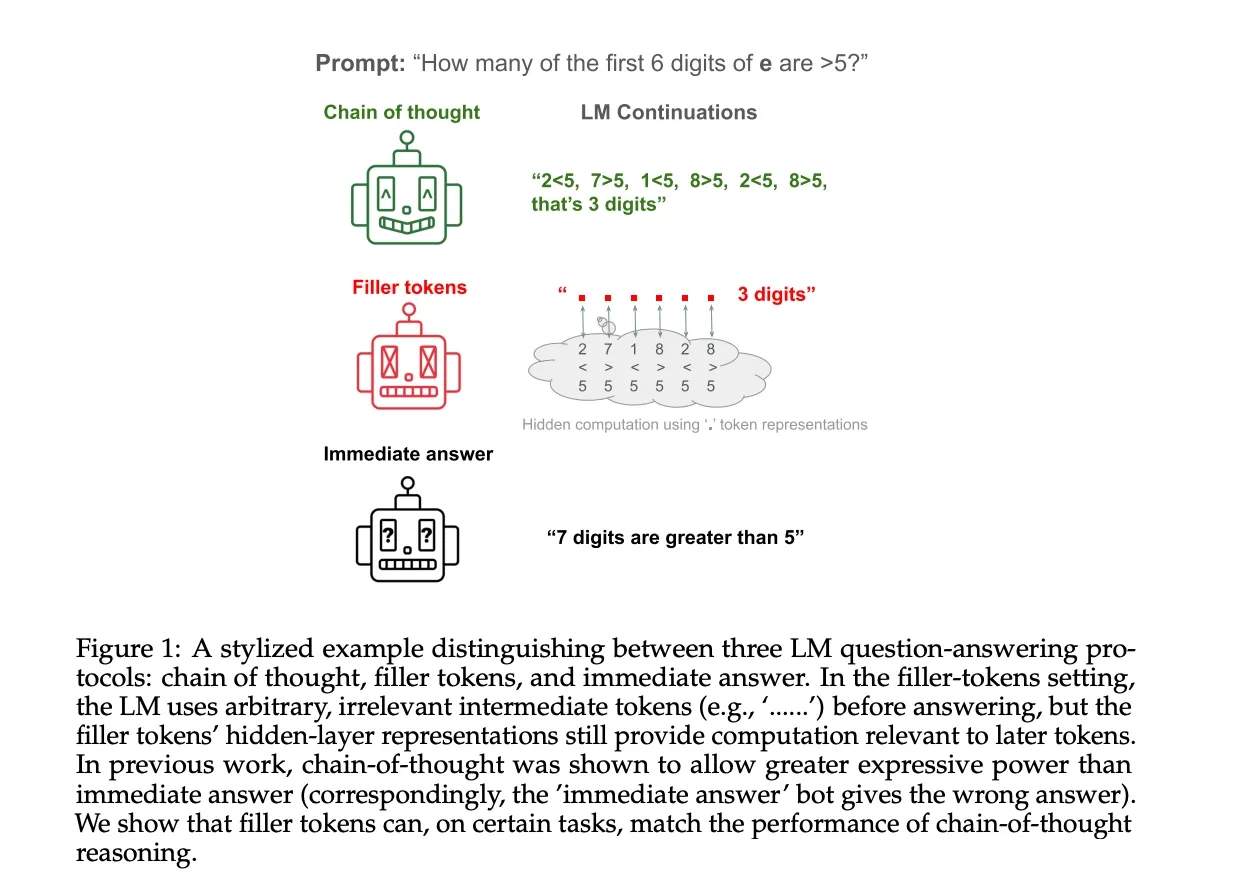

In their paper, “Let’s Think Dot by Dot,” Pfau et al. (2024) investigate whether the performance gains from chain-of-thought are due to interpretable reasoning or simply the greater computation that additional tokens allow. They demonstrate that for certain algorithmic tasks, transformers can use meaningless “filler tokens” (e.g., ’…’) to perform complex, hidden computations, achieving high accuracy on problems they could not solve when forced to respond immediately. For example, on a sufficiently complex 3SUM task, models using filler tokens reached 100% accuracy, whereas models without them were only 66% accurate. This suggests the critical bottleneck is the computational limitation of a single forward pass, not the semantic content of the tokens. The sequence of filler tokens provides the model with a “scratchpad” for multi-step reasoning, directly challenging the assumption that a model’s intermediate steps must be linguistically meaningful to be computationally effective.

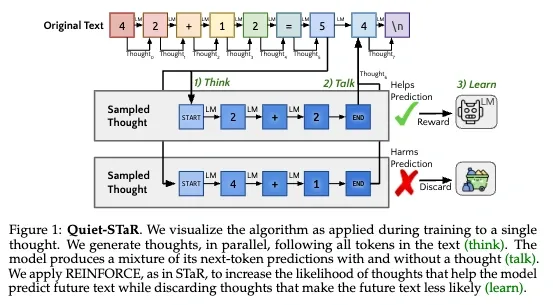

Zelikman et al. (2024) developed Quiet-STaR, employing learnable tokens to mark boundaries of internal rationales. This approach enabled language models to infer unstated reasoning steps, improving generalization without task-specific fine-tuning. The system generated token-level rationales internally (one hidden “explanation” per token produced) without outputting them, essentially “thinking before speaking” in a fine-grained way.

Continuous latent reasoning (2024-2025)

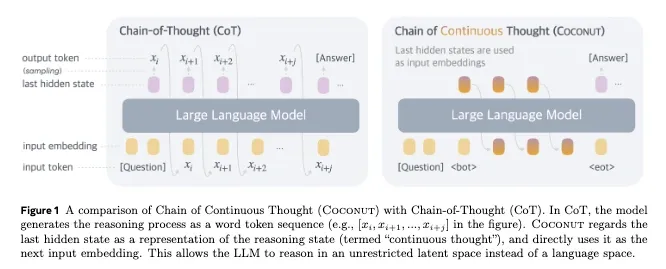

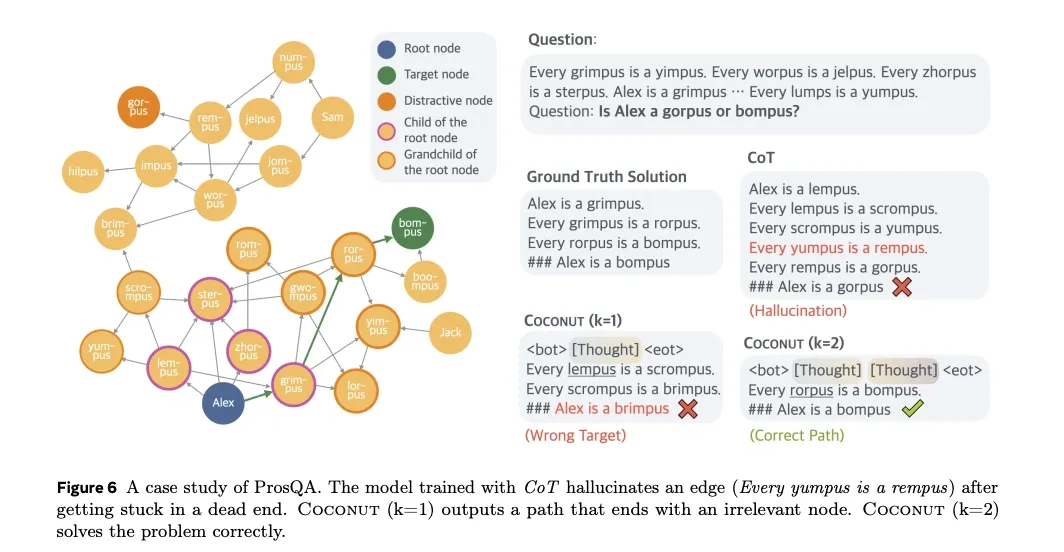

A representative example is Hao et al. (2024) and their COCONUT (Chain of Continuous Thought) architecture. Instead of sampling a discrete token at each reasoning step, COCONUT feeds the model’s last hidden states as the next-step input embeddings, delaying the projection to the vocabulary until the final answer.

Technically, COCONUT operates by:

- Processing the input question normally through the transformer.

- Taking the final hidden state (a high-dimensional vector, typically 2048-4096 dimensions).

- Instead of projecting to vocabulary and sampling, directly feeding this vector back as the “next token” embedding.

- Repeating this process for multiple latent reasoning steps.

- Only projecting to vocabulary for the final answer.

A 4,096-dimensional activation vector, even after aggressive 4-bit quantization, contains 16,384 raw bits (far more than a single discrete token, which carries at most log₂(50,000) ≈ 16 bits). However, directly comparing raw bits can be misleading because these representations differ significantly in information density. A token from a 50k-word vocabulary, compressed by Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE), packs information very densely, though in practice, due to redundancy in natural language, tokens typically contain even fewer effective bits of information. For instance, LLaMA-2-70B achieves a perplexity of 3.32 on WikiText-2, meaning each token effectively encodes only around 1.73 bits of meaningful information (Chen et al., 2025).

Activation vectors, on the other hand, are large and redundant by design. Recent compression methods like Multi-Head Latent Attention (MLA) from DeepSeek-V3 (Liu et al., 2024) show these vectors can be compressed by a large factor while keeping quality. This implies each activation value may effectively contain around 0.11 bits, translating to roughly 460 meaningful bits for the entire 4,096-dimensional vector.

Even with redundancy, activation vectors still carry much more usable information (approximately 460 bits vs. 1.73 bits per token). This suggests latent reasoning has more representational bandwidth than reasoning purely at the token level.

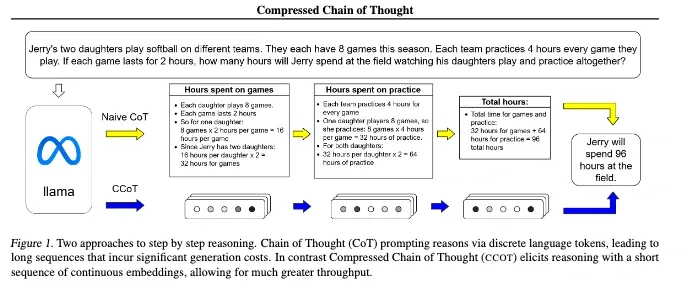

In their 2024 paper, Cheng and Van Durme (2024) introduced Compressed Chain-of-Thought (CCoT), a framework that utilizes a dual-module architecture. A CCOT module (parameterized by φ) generates a sequence of dense “contemplation tokens,” which serve as compressed representations of an entire reasoning chain. A second DECODE module (parameterized by ψ) then uses these tokens to produce the final answer. This approach demonstrates that complex reasoning can be effectively summarized in continuous representations. However, contrary to methods that process steps in parallel, CCoT generates these contemplation tokens autoregressively, meaning they are produced sequentially one after another.

Liu et al. (2024) proposed Hidden Chain-of-Thought (HCoT), training auxiliary models to generate compact thought representations that maintain semantic richness while drastically reducing computational overhead. Their method compresses each intermediate reasoning step into a special [CoT] token, interleaving these compressed thoughts with the generated content.

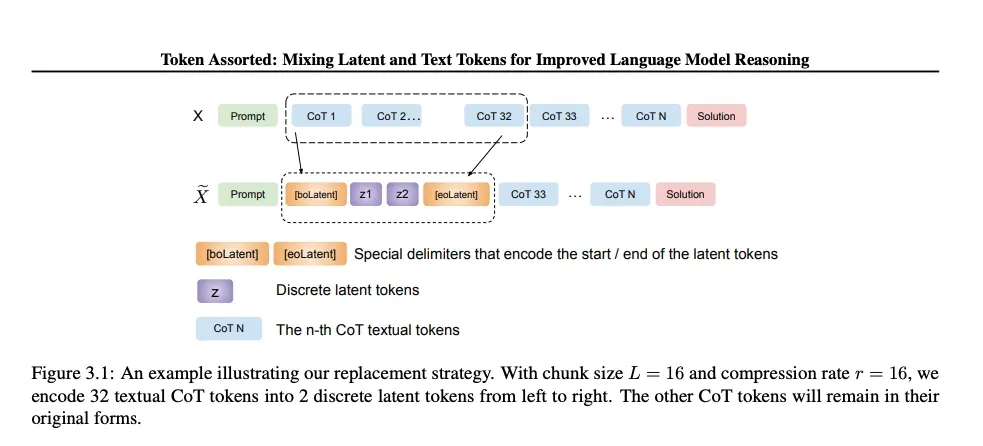

Token Assorted (Su et al. (2025)) took a hybrid approach, using a VQ-VAE to encode early reasoning steps into latent codes while keeping later, critical steps in text. This model reduced the length of reasoning traces by an average of 17% while maintaining interpretability where needed.

Architectural innovations (2025)

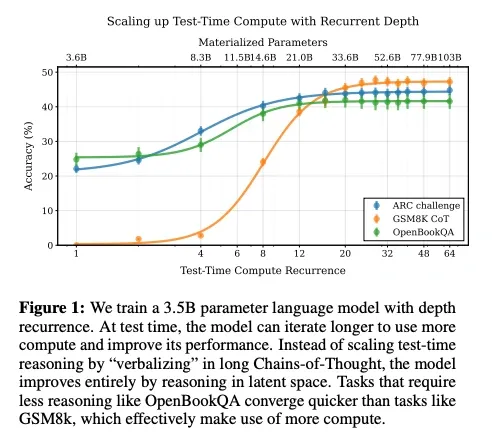

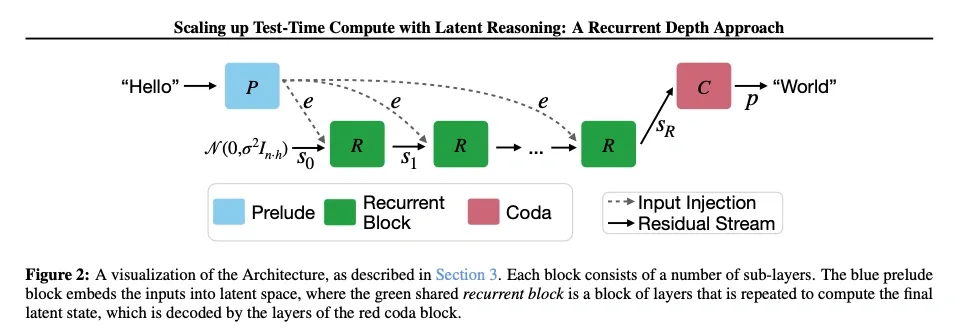

Recent work has focused on architectural modifications that natively support latent reasoning. Geiping et al. (2025) introduced Huginn, a recurrent framework enabling adaptive computation allocation through RNN-like iterative processing. The architecture consists of:

- Prelude layers that encode the input into a latent state.

- A recurrent core of Transformer blocks applied repeatedly.

- A coda that decodes the final answer.

This design untied computation depth from layer count, allowing a 3.5B model to achieve 50B-model performance through approximately 32 recurrent iterations.

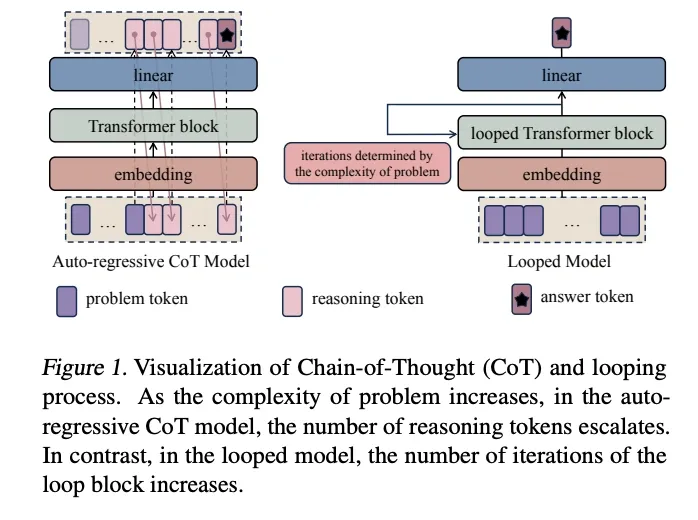

In “Enhancing Auto-regressive Chain-of-Thought through Loop-Aligned Reasoning,” Yu et al. (2025) introduce RELAY (REasoning through Loop Alignment iteratively), a two-stage framework designed to improve how auto-regressive models handle long reasoning tasks. The method bridges the gap between auto-regressive models, which often struggle with generating accurate, long Chain-of-Thought (CoT) sequences, and Looped Transformers, which have strong length generalization capabilities but limited versatility.

The RELAY framework first trains a Looped Transformer by aligning its internal loop iterations with the explicit reasoning steps of a CoT process. This allows the Looped Transformer to generate accurate, high-quality reasoning chains for problems that are more complex and longer than those in its original training data. These generated chains are then used as a new, high-quality dataset to fine-tune a standard auto-regressive model, significantly enhancing its performance on complex reasoning tasks that require generalization to longer problem lengths.

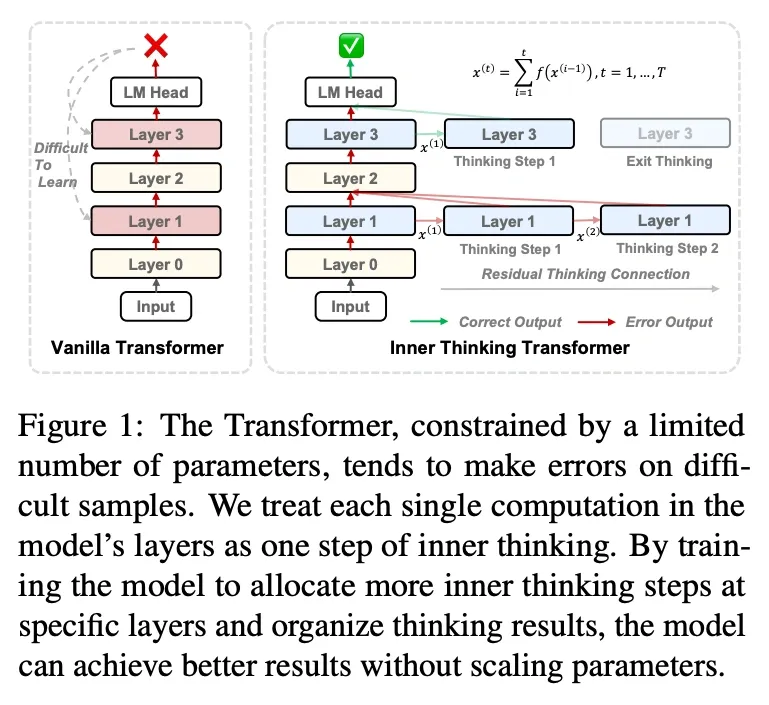

Chen et al. (2025) proposed the Inner Thinking Transformer (ITT), treating each transformer layer as a discrete reasoning step with adaptive token routing and residual refinement.

Mechanisms of continuous latent reasoning

Core Architecture

Continuous latent reasoning fundamentally alters the information flow in transformer architectures. In traditional models, the transformation sequence follows:

Input Embeddings → Transformer Layers → Projection to Vocabulary → Sampling → Next Token

Continuous reasoning architectures bypass the projection bottleneck:

Input Embeddings → Transformer Layers → Direct Hidden State Reuse

The mathematical formulation involves modifying the standard transformer update. Instead of:

Latent reasoning uses:

Where ProjectToEmbed is typically a learned linear transformation that maps the hidden state back to the embedding dimension.

Training Methodologies

Building a model that genuinely “thinks in vectors” is less about inventing huge new architectures and more about guiding the network away from the crutch of language without wrecking its performance. Current practice has converged on the following five-part recipe.

1 · Curriculum-guided latentisation

Training still starts with ordinary chain-of-thought (CoT), but every epoch hides a growing fraction of those intermediate words and asks the model to run directly on their hidden-state vectors.

- COCONUT runs through the corpus in seven discrete stages. At stage 0 no rationale tokens are hidden; by the final stage roughly 85 % of every rationale is replaced by its own activations. Each new stage is introduced only after perplexity has stabilised, so the network never “forgets how to read”.

- Stepwise Internalisation removes chain-of-thought (CoT) tokens from the beginning of the reasoning sequence in a continuous, linear fashion. With each training epoch, more tokens are hidden from the start of the rationale, forcing the model to internalise the initial steps of the reasoning process. A technique called “Removal Smoothing” introduces a small amount of randomness to the number of tokens being removed, which helps to stabilize training as the model learns to operate on increasingly truncated context.

Hidden tokens receive no direct loss; visible tokens and the final answer are trained with the usual cross-entropy.

2 · Hidden-state distillation and self-distillation

Once the network can survive missing words, the next step is to make its latent trajectory mimic a teacher that still reasons out loud.

- Implicit CoT (ICOT) records the layer-wise activations of a frozen teacher and trains a student to match them (often with an MSE loss) while still predicting the final answer. On GPT-2 Small, the paper reports a 4–8× inference-time speed-up versus explicit CoT (task-dependent), along with an accuracy drop that grows with task difficulty (e.g., >20 points on GSM8K and ~90 points on 5×5 multiplication).

- CODI runs the same set of weights twice: once with text and once with latent thoughts, and aligns only the hidden state immediately before the answer token. Because there is no separate teacher, CODI matches explicit-CoT accuracy on GSM8K while cutting context length by about a factor of three.

3 · Compact latent tokens

ICOT-style distillation still leaves “one vector per hidden step”. The next advance packs many steps into a handful of learned embeddings.

- CCoT generates a short sequence of “contemplation tokens”, typically 30–50 % as long as the full CoT. An auxiliary decoder can reconstruct the dropped text for auditability.

- HCoT collapses an entire rationale into a single placeholder token

[CoT]. A contrastive InfoNCE loss pushes two placeholders apart unless they decode to the same complete rationale, producing dense, semantically clustered codes. - Token Assorted compresses only the early reasoning hops into VQ-VAE codes and leaves the final, safety-critical steps in natural language, shaving about 15–20 % off the trace length while preserving human-readable checks.

4 · Recurrent or loop-aligned supervision

Some architectures keep sequence depth fixed and let the model loop through shared blocks as many times as it needs.

- Huginn splits the network into Prelude, Shared Core and Coda blocks. During pre-training it is unrolled 1 – 32 times at random. Cross-entropy is applied only to the final (and optionally the last few) iterations, and a small KL-style stability term limits drift between successive hidden states. At inference a learned halting gate decides when to stop looping.

- RELAY first aligns each loop iteration with the next step of a known CoT, then freezes that looped model and distils its internal trace into a standard auto-regressive decoder. The distilled model scores about 10–12 points higher than an equal-size plain decoder on long-division benchmarks.

- Inner Thinking Transformer (ITT) adds a lightweight linear probe after every residual block that predicts the current sub-answer. The probe and the main weights are trained jointly, and an adaptive token router lets tokens judged “easy” skip further passes, saving roughly one-quarter of the total compute without hurting accuracy.

5 · Hybrid latent reinforcement learning

Supervised data eventually tops out, so teams switch to reinforcement learning that rewards correctness and charges for extra computation.

Hybrid Reasoning Policy Optimisation (HRPO) is the flagship:

- At every generation step the network mixes two embeddings (a normal token embedding and a transformed copy of the previous hidden state) weighted by an action variable

gamma. - The reward is 1 for a correct final answer, minus a small fee per visible token and per latent iteration (instances where

gamma≠ 0). - HRPO is trained with Group Relative Policy Optimisation (GRPO), which uses the mean reward of a mini-batch of roll-outs as its baseline instead of a learned critic. GRPO needs about half the memory of PPO and converges just as fast.

Setting the step penalty too low makes the model talk verbosely; setting it too high drives it into silent, brittle reasoning. Authors report that a short grid search over a few hundred prompts is enough to find the sweet-spot penalty.

6 · Generic efficiency add-ons

Three auxiliary techniques, first devised for token-level RL, carry over cleanly to the latent regime:

- GRPO itself, supplying a critic-free baseline.

- Adaptive Length Penalty (ALP), which scales the per-step cost inversely with the model’s real-time solve-rate, trimming median reasoning length by ~50 % without hurting hard cases.

- AdaRFT introduces an adaptive curriculum for reinforcement finetuning. It works by dynamically adjusting the difficulty of training problems to match the model’s current skill level. Based on the model’s recent reward signals, it selects problems that are challenging but still solvable. This adaptive sampling avoids wasting computation on problems that are too easy or too hard, which in turn keeps the reward signal rich and informative for more efficient learning.

A modern training run at a glance

- Supervised warm-up on full CoT.

- Curriculum latentisation for five to ten epochs (COCONUT or Stepwise Internalisation).

- Hidden-state distillation, optionally followed by compact latent token training (CCoT or HCoT).

- Architecture-aligned pre-training if you use loops (Huginn, RELAY, ITT).

- Hybrid RL fine-tuning with HRPO + GRPO, optionally adding ALP and AdaRFT.

Representational dynamics

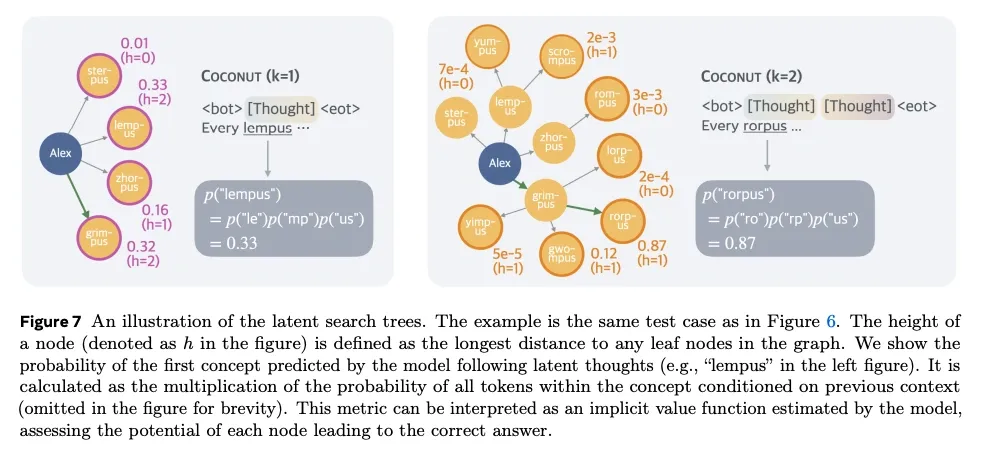

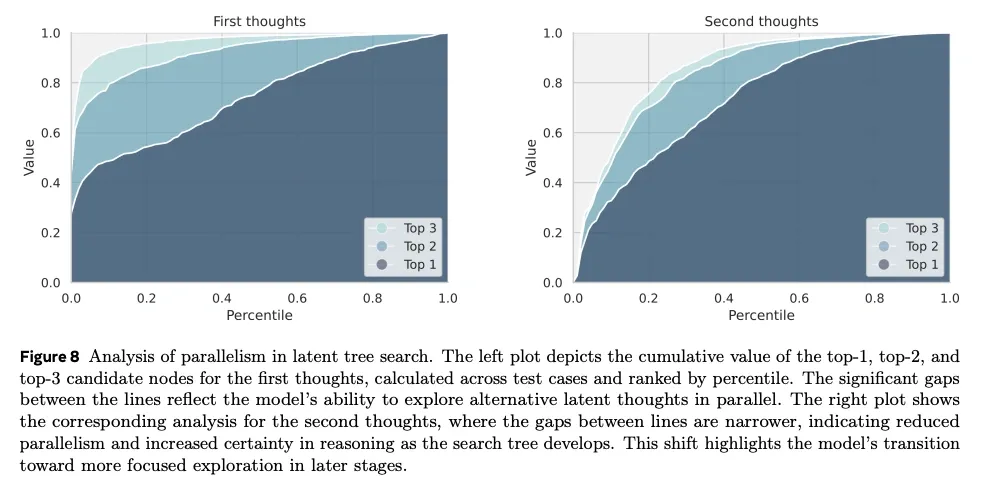

Analysis of COCONUT’s latent reasoning reveals a process more complex than a simple linear chain. Instead of committing to a single path, the continuous thoughts can be interpreted as a latent search tree that explores multiple potential next steps simultaneously.

- Parallel reasoning paths. The paper argues that a single “continuous thought” can encode multiple branching hypotheses. This is shown by forcing the model to decode its latent state back into language; the probability distribution over possible next words suggests several reasoning paths are being tracked at once. In their logical reasoning example, the model stays uncertain after the first continuous thought but identifies the correct path after the second, consistent with pruning.

-

Implicit value function. This latent search is not uniform. The model appears to prioritize more promising paths and prune less relevant ones. The paper refers to the probability distribution over potential next steps as an “implicit value function.”

-

From exploration to focus. The paper reports that early continuous thoughts keep more diversity (several alternatives in parallel). Later thoughts narrow toward a smaller set of candidates, which they frame as an implicit search process.

Engineering constraints

So far, latent reasoning systems come with costs you don’t see in ordinary Chain‑of‑Thought models. The literature converges on six broad constraints:

1. A curriculum is mandatory (otherwise the model never “gets” latent reasoning)

COCONUT’s ablation shows that training directly on (question, answer) pairs with hidden‑state recycling performs worse than a no‑CoT baseline. Only the staged schedule that first teaches the model to reason in language and then incrementally replaces early steps with vectors seems to drive the gains. In their “w/o curriculum” run, GSM8K drops from 34.1% to 14.4%. Designing such curricula (and automatically tuning them for new domains) remains an open research problem.

2. Latent loops break GPU parallelism

Because every continuous thought depends on the previous hidden state, training (and inference) cost scales with the number of latent steps, not the batch size. COCONUT explicitly notes that it must execute n + 1 forward passes for n thoughts, and that “the sequential nature of the multiple forward passes poses challenges for parallelism.” This serial dependency throttles throughput on modern GPU clusters built for large‑batch matrix multiplies.

3. KV‑cache memory becomes the new bottleneck

Long latent traces keep the token sequence constant. They still enlarge the key/value cache: every extra iteration stores another set of 64‑bit vectors. Recent work on SQuat (Wang et al. (2025)) shows that even with aggressive INT‑2 quantisation the cache can dominate peak GPU memory when models “think” for dozens of steps. Compression helps but introduces accuracy/latency trade‑offs that are not yet well understood.

4. Knowing when to stop is still heuristic

During inference a latent‑reasoning model must decide when to emit an <eot> and return to language space. Current systems either pad to a fixed depth or train an ad‑hoc binary classifier over hidden states, and COCONUT reports that both heuristics work “comparably well.” Huginn trains a learned halting classifier (§4.1, p 5) which shows promise but still requires careful tuning. Neither approach adapts gracefully to problem difficulty, and mis‑predictions manifest as truncated explanations or runaway loops.

5. Deep recurrent stacks risk optimisation instability

Recurrent‑depth architectures such as Huginn push performance by unrolling a shared core 30+ times, but the authors note that gradient signals weaken as depth grows, requiring careful learning‑rate scaling and residual gating to avoid divergence. Balancing depth‑on‑demand with stable training dynamics is still an active area of study.

6. Tooling for debugging and evaluation is immature

A survey of efficient reasoning methods highlights a “complexity of latent‑space implementation” gap: without textual traces, it is hard to verify correctness, attribute errors, or measure reasoning efficiency. New metrics (e.g., embedding‑consistency scores) and visual probes are being proposed, but no standard evaluation suite exists yet.

Interpretability limits

The “neuralese” problem

Lindsey et al. (2025) argues that models can implement complex computations via feature interactions. If intermediate reasoning happens as continuous vectors, you can end up with an internal “neuralese” that does not map cleanly to words. Unlike discrete tokens (which at least map to a vocabulary), a continuous thought is a 4096‑dimensional vector with no obvious interpretation.

Key challenges include:

- The same reasoning can be encoded in many equivalent ways (rotation/scaling invariance).

- Information is distributed across dimensions, not localized.

- The “meaning” of directions can shift with context.

Emerging Interpretability Techniques

Some approaches:

-

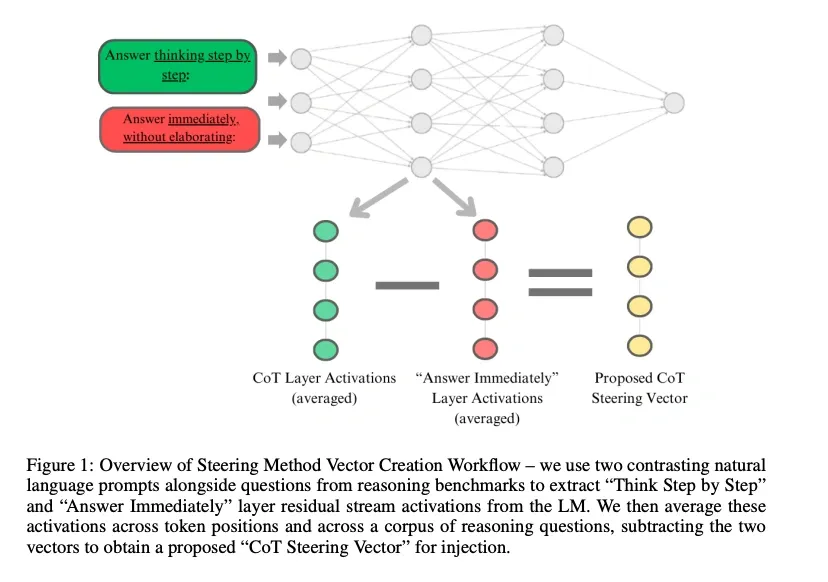

Geometric analysis looks for directions in activation space correlated with reasoning (Zhang and Viteri, 2025). One construction is:

reasoning_vector = h_with_cot - h_without_cot h_enhanced = h_input + α * reasoning_vector

- Probing methods try to map latent states back to interpretable signals, for example:

- linear probes that predict intermediate answers from latent states

- contrastive learning that aligns latent states with text descriptions

- low-dimensional projections for visualization

Even with these methods, full interpretability remains elusive. We can sometimes detect that reasoning is happening, but not the detailed how.

Alignment considerations

If intermediate steps aren’t readable, some of the usual safety hooks get weaker:

- A model could learn latent strategies that look fine in final text but rely on shortcuts or biases.

- Verification is harder because you can’t easily inspect intermediate steps for spurious correlations.

- Output filtering only sees the final text; the risky computation happens earlier.

Some mitigation ideas:

- Occasionally force explicit reasoning and compare it to the latent trajectory.

- Train secondary models to probe latent trajectories for specific failure modes.

- Keep parallel explicit and latent streams and cross-check them.

Current applications and performance

Mathematical Reasoning (GSM8k)

On the GSM8k math reasoning dataset, the performance of continuous reasoning is more nuanced.

COCONUT reaches 34.1% accuracy (vs. 16.5% for a no-CoT baseline), but it does not surpass the standard Chain-of-Thought baseline (42.9%). The main win here is efficiency: it reduces reasoning tokens from 25.0 (CoT) to 8.2.

Logical Reasoning (ProntoQA & ProsQA)

COCONUT shows its largest gains on logical reasoning tasks that require planning and searching.

On ProntoQA, COCONUT reaches 99.8% accuracy vs. 98.8% for CoT. On ProsQA, it reaches 97.0% vs. 77.5% for CoT. The reported gains come with fewer reasoning tokens than CoT, because the model can do more intermediate work in continuous states instead of emitting long textual traces.

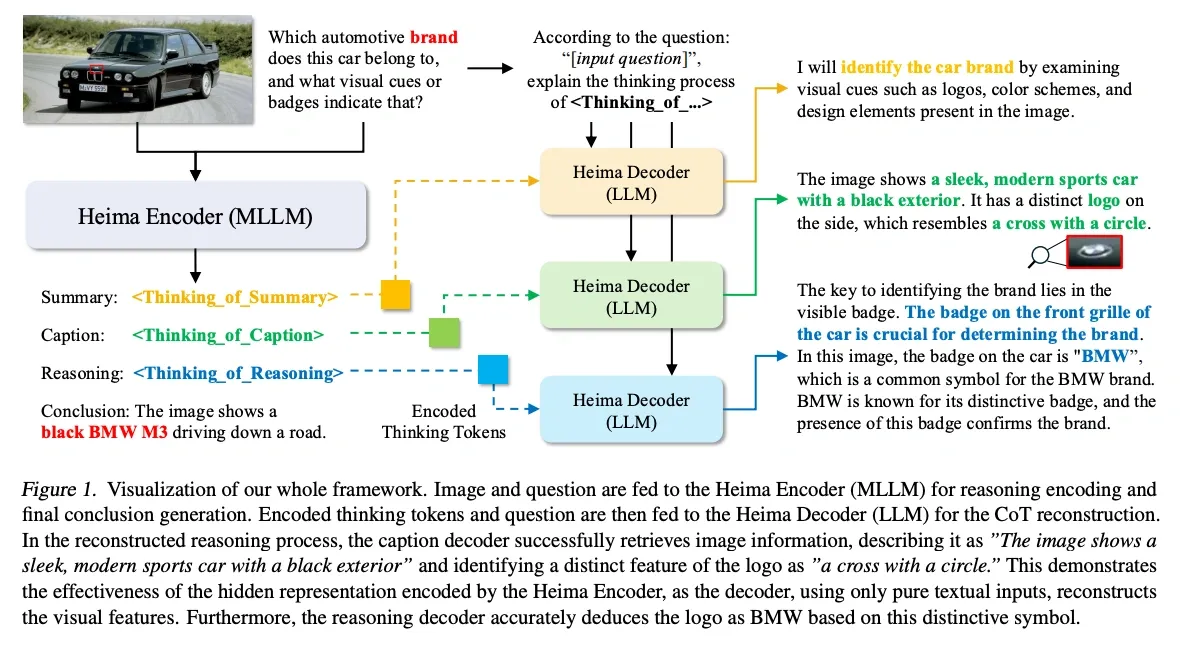

Multimodal Integration

Heima (Shen et al. (2025)) reported that “thinking tokens” work well for multimodal reasoning. In their setup:

- It reduces the number of reasoning tokens (reported as low as 6% of the text-based baseline in some settings).

- It can keep accuracy comparable to text-based approaches while avoiding the “description bottleneck” of converting visual concepts into words.

- Its latent “thinking tokens” can encode visual information that can be decoded back into text descriptions even without access to the original image.

Code Generation and Formal Reasoning

Potential fits:

- Latent states can maintain program state, variable bindings, and control flow without verbose comments.

- Some abstract relationships may be easier to represent as vector transformations than as symbolic strings.

- For planning tasks, the COCONUT paper reports lower inference time on ProsQA (0.15s vs 0.47s for CoT), consistent with the idea that latent reasoning can reduce token overhead.

Where latent reasoning might help

Efficiency and token overhead

Long chain-of-thought traces can be expensive because attention cost grows with context length. A simplified way to think about the trade-off:

- Traditional CoT grows external context length with each reasoning step, which pushes attention cost toward a quadratic curve in the number of steps.

- Latent reasoning keeps the external context length closer to constant and spends extra compute in internal steps. Total cost still grows with the number of latent steps, but memory and KV-cache behavior can be friendlier because you are not appending long textual traces.

Representation without text

Latent steps can carry intermediate state without serializing it into tokens. That can make some kinds of search or planning more efficient, but it also makes intermediate reasoning harder to inspect.

One (oversimplified) mental model is mixing multiple partial hypotheses into a single hidden representation:

-

Parallel hypothesis exploration. Unlike sequential text, vectors can superpose multiple reasoning branches. For example:

Empirically, COCONUT’s ablation on p 4 shows wider hidden states boost success on ProsQA, consistent with superposition.

-

Continuous optimization. Latent steps are differentiable, so in principle you can search in representation space rather than only by sampling tokens.

-

Emergent algorithms. Internal procedures can resemble classical algorithms (dynamic programming, branch-and-bound) without being explicitly programmed.

Architecture and scaling notes

Recent findings from Ye et al. (2025) provide new insights into how model architecture affects reasoning:

- For complex reasoning tasks, depth (number of layers) can matter more than width for a fixed parameter budget. For example, the paper reports a deeper, smaller model (16-layer, 576-dim) outperforming a shallower, larger model (4-layer, 1920-dim) on math problems with longer reasoning chains.

- Models can also learn to produce shorter solutions when trained with objectives that reward efficiency, which reduces wasted computation on unnecessary intermediate steps.

Integration with Reinforcement Learning

Latent reasoning connects naturally to RL:

-

Direct trajectory optimization. RL rewards can shape latent paths without language bottlenecks. For example:

-

Self-play and exploration. Models can explore reasoning strategies in latent space faster than generating long text traces.

A speculative design sketch

If you want to combine the ideas above into one system, a reasonable sketch is: let the model decide, step by step, whether it should emit a text token or run extra latent steps, and make the number of latent steps adaptive.

This is a design sketch. There are other plausible designs; I’m using this one to make the trade-offs concrete.

What the architecture might look like

-

A recurrent “core” that can run for k inner iterations at inference time. Extra reasoning costs compute rather than parameters.

-

A gate that mixes a normal token embedding with a transformed copy of the previous hidden state. For example:

Early in training, you would likely push toward 0 (pure language) and gradually increase it with a curriculum so the model learns to reuse hidden states. Because the gate is differentiable, the model can still fall back to language when explicit text is useful.

-

(Optional) A small latent memory (for example, a handful of vectors) updated per inner loop, to keep multiple hypotheses alive without having to externalize them as text.

What you’d need to validate

- Training stability when mixing token and latent steps.

- Evaluation that doesn’t rely on readable CoT traces.

- Interpretability hooks (forced reveal steps, probes) that work at scale.

I haven’t implemented this; treat it as a sketch for thinking about system design, not as a claim that it is practical or superior.

Latent-space reasoning is promising because it can move more intermediate computation into dense vectors instead of emitting long token traces. The trade-off is that it can be harder to interpret, debug, and evaluate. Progress here will likely depend on better training stability, clearer evaluation protocols, and stronger interpretability hooks.

References

Chen, M., Shao, W., Xu, P., Wang, J., Gao, P., Zhang, K., & Luo, P. (2025). EfficientQAT: Efficient Quantization-Aware Training for Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.11062. https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.11062

Chen, X., Wang, L., & Li, Y. (2025). Inner Thinking Transformer: Leveraging Dynamic Depth Scaling to Foster Adaptive Internal Thinking. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.13842. https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.13842

Chen, X., Zhao, A., Xia, H., Lu, X., Wang, H., et al. (2025). Reasoning Beyond Language: A Comprehensive Survey on Latent Chain-of-Thought Reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.16782. https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.16782

Cheng, P., & Van Durme, B. (2024). Compressed Chain-of-Thought: Efficient reasoning through dense representations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.13171. https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.13171

Deng, Y., Choi, Y., & Shieber, S. (2024). From Explicit CoT to Implicit CoT: Learning to Internalize CoT Step by Step. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.14838. https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.14838

Liu, A., Feng, B., Xue, B., Wang, B., Wu, B., Lu, C., Zhao, C., Deng, C., Zhang, C., Ruan, C., et al. (2024). DeepSeek-V3 Technical Report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.19437. https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.19437v1

Deng, Y., Prasad, K., Fernandez, R., Smolensky, P., Chaudhary, V., & Shieber, S. (2023). Implicit Chain-of-Thought reasoning via knowledge distillation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.01460. https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.01460

Geiping, J., Fowl, L., Somepalli, G., Goldblum, M., Moeller, M., Goldstein, T., & Jacobs, T. (2025). Scaling up test-time compute with latent reasoning: A recurrent depth approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.05171. https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.05171

Goyal, A., Bengio, Y., Weston, J., & Ballas, N. (2023). Think before you speak: Training language models with pause tokens. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.02226. https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.02226

Hao, S., Gu, Y., Ma, H., Hong, J., Wang, Z., Wang, D., & Hu, Z. (2024). Training large language models to reason in a continuous latent space. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.06769. https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.06769

Lindsey, R., Kenton, Z., Everitt, T., Wattenberg, M., Mirhoseini, A., Leike, J., & Amodei, D. (2025). Circuit tracing: Revealing computational graphs in language models. Transformer Circuits Thread. https://transformer-circuits.pub/2025/attribution-graphs/biology.html

Liu, J., Chen, X., Wang, H., Zhang, L., & Li, M. (2024). Expediting and elevating large language model reasoning via hidden chain-of-thought decoding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.08561. https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.08561

Pfau, J., Merrill, W., & Bowman, S. R. (2024). Let’s think dot by dot: Hidden computation in transformer language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.15758. https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.15758

Shao, Z., Wang, P., Zhu, Q., Xu, R., Song, J., et al. (2024). DeepSeekMath: Pushing the Limits of Mathematical Reasoning in Open Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.03300. https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.03300

Shen, H., Wu, Y., Chen, K., Wang, J., & Zhang, Q. (2025). Efficient reasoning with hidden thinking. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.19201. https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.19201

Shen, Z., Yan, H., Zhang, L., Hu, Z., Du, Y., & He, Y. (2025). CODI: Compressing Chain-of-Thought into Continuous Space via Self-Distillation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.21074. https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.21074

Shi, T., Wu, Y., Song, L., Zhou, T., & Zhao, J. (2025). Efficient Reinforcement Finetuning via Adaptive Curriculum Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.05520. https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.05520

Su, Y., Liu, T., Wang, D., Chen, H., & Zhou, J. (2025). Token Assorted: Mixing latent and text tokens for improved language model reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.03275. https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.03275

Wang, H., Han, L., Xu, K., & Srivastava, A. (2025). SQuat: Subspace-orthogonal KV Cache Quantization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.24358. https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.24358

Xiang, V., Blagden, C., Rafailov, R., Lile, N., Truong, S., Finn, C., & Haber, N. (2025). Just Enough Thinking: Efficient Reasoning with Adaptive Length Penalties Reinforcement Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.05256. https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.05256

Yang, K., Klein, D., Pang, N., & Sachan, M. (2024). Do large language models latently perform multi-hop reasoning? arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.16837. https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.16837

Ye, H., Zhang, C., Wang, X., Liu, Y., & Sun, M. (2025). Scaling laws for reasoning: The importance of model depth. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.20311. https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.20311

Yu, D., Wang, S., Chen, L., Zhang, M., & Li, X. (2025). Enhancing auto-regressive Chain-of-Thought through loop-aligned reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.08482. https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.08482

Zelikman, E., Wu, Y., Mu, J., & Goodman, N. D. (2022). STaR: Bootstrapping reasoning with reasoning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35, 15476–15488. https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.14465

Zelikman, E., Harik, G., Shao, Y., Jayasiri, V., Haber, N., & Goodman, N. D. (2024). Quiet-STaR: Language models can teach themselves to think before speaking. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.09629. https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.09629

Yue, Z., Jin, B., Zeng, H., Zhuang, H., Qin, Z., Yoon, J., Shang, L., Han, J., & Wang, D. (2025). Hybrid Latent Reasoning via Reinforcement Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.18454. https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.18454

Zhang, T., & Viteri, M. (2025). Uncovering latent Chain-of-Thought vectors in language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.14026. https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.14026